Petruschki`s Journey Into The Blue - Chapter 12 - Hans Hartung and the Beatles - Nicolas de Staël

Cover photo: Nicolas de Staël Fleurs dans un vase Bleu 1953 by Cea. liscensed under CC BY 2.

"Explore the void to its limits."

Nicolas de Staël

Who was Nicolas de Staël?

I have to admit that I had never heard of him before. Although he is considered one of the most prominent artists of the French post-war period. But he, too, was forgotten for a long time. Only since maybe 10/15 years there are exhibitions again and his paintings are sold for a lot of money.

Portrait of Nicolas de Staël drawn by Yan Ten Kate in 1937

Maybe that's why this chapter comes into being. Because I am always so happy to discover someone whose paintings I would like to see in an exhibition, whom I would like to face, with all their brushstrokes and masses of paint. The cover picture Flowers in a blue vase from 1953 is from him.

I re-enter an unknown, infinite land and quickly lose myself. And lose me so quickly. Everything I record suddenly makes my journey very slow, as if in slow motion I fly with stretched wings through the 1950s and the successful years of abstract painting. How long did it take to become significant…. ? And I keep sliding back on the air currents to 1907. In this year the art historian Wilhelm Worringer published his doctoral thesis: “Abstraktion und Einfühlung" (Abstraction and empathy). It says: "The tendency towards abstraction is the result of a deep insecurity of people in relation to the world."

In the same year Hilma af Klint painted the first pictures “The Big Ten”, and František Kupka also painted abstract. Kandinsky created “the first abstract picture” sometime a few years later and wrote his groundbreaking text: “Über das Geistige in der Kunst” (On the Spiritual in Art) in 1911. And there were many others: Sonia Delauney-Terk (born 1885), Robert Delauney (b .1885), Picabia (born 1878), Mondrian (born 1872), Sophie Taeuber-Arp (born 1989) and more and more. Then came two long, devastating wars. Paris became the center of abstract art. During World War II under the occupation of the Nazis, abstract art could only happen underground and was part of the Resistance.

In the post-war period, the Nouvelle École de Paris was created, a loose combination of artists from Tachism and Art Informel. It included Nicolas de Staël and Hans Hartung. And I lose myself, fluttering rather than flying in the biographical. What, for Nicolas de Staël, means a journey through the cliché of the exciting, tragic life of an artist who in the end may break down because of love and excessive demands.

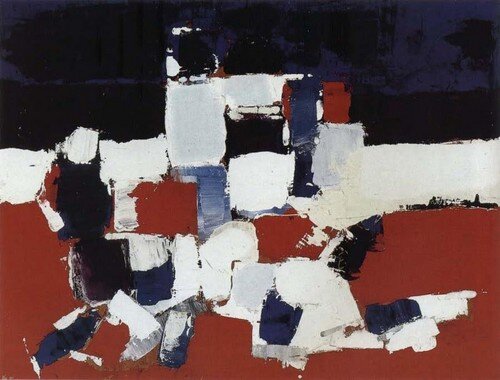

Nicolas de Staël Marché Afrique seen at solitudemonamour.blogspot.com

On this painting “Marché Afrique” you can see the impasto application of the colors. This turns the picture into a relief that is incredibly lively and sensual.

"The instinct is of unconscious perfection and my pictures live on conscious imperfection."

Nicolas de Staël

In the German Wikipedia article about Nicolas de Staël it is mentioned that the painter Christine Boumeester inspired him for abstract art in Nice. She had first devoted herself to surrealist painting and came to abstraction through Hans Hartung. Somewhere in the back of my mind I thought I read that she brought Hartung and de Staël together. But I just couldn't find it anymore. In the Wikiwand article it is said that the Belgian painter Madeleine Haupert, who herself was at the Paris Art Academy, introduced him to abstraction. He wrote to her:

“Dear Madeleine Haupert ... In memory of our questions, our problems, our fears as beginning painters, also our hopes, I tell you ... work for yourself, only for you. It's the best of us ... I've lost my universe and my silence. I'm going blind .... Being nobody for others and everything for myself ... If you have not yet lost your world, guard it jealously, defend it against invasion; I'm dying ... "

Hartung and de Staël moved in the same artistic circles and had the same friends. And the wonderful gallery owner Jeanne Bucher was connected to both of them. She had exhibited works of Cubism and Surrealism in her gallery as early as 1925. During the occupation of France by the German National Socialists in World War II, she exhibited the works of ostracized artists despite all the threats. In the thirties Hartung was able to store his pictures with her. De Staël and his family supported them. Among other things, it gave them the opportunity to live in a country house. In 1944 she had Nicolas de Staël's first solo exhibition in Paris.

And there is still a connection from today. In 2016 there was the exhibition Vibration of Space - Heron, de Staël, Hartung, Soulages at the London gallery Waddington Custot.

The painter Patrick Heron believed that a “vibration of space” would be created by applying the materiality of the paint, which produced a visible grain on the surface of the painting. So to speak ... as soon as you paint, the room vibrates. For him a key element that he brought into his own work at that time and that he valued so much in the work of Hartung, Soulages and de Staël.

With “Vibration of Space” I think of Hartung's attempts to paint the vibrations of the universe, of Hilma af Klint's voices from the universe. Now we also have Nicolas de Staël as a universe painter.

“You never paint what you see or think you see. With a thousand vibrations you paint the blow that you have received, that you will receive, similar, different. " Nicolas de Staël in a letter to Roger von Gindertael

And here some more wonderful physics: Die Erde, sie summt und singt und brummt.

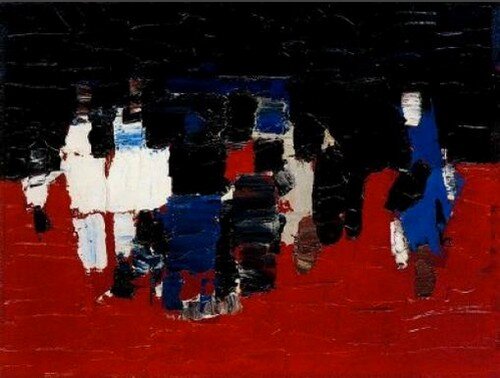

Nicolas de Staël Marine

Nikolai Vladimirovich Stael von Holstein was born in St. Petersburg in 1914. The family was close to the tsar and they had to flee from the revolution. His parents died early in exile in Poland. He and his two sisters grew up in Brussels with wealthy family friends.

From 1933 he studies art at the Academy Beaux-arts de Bruxelles.

He traveles through France and Spain. He even sells a picture in Barcelona. Hardly anything is left of his early work. Until the mid-1940s, he kept destroying his pictures.

In Morocco he meets Jeannine Guillon, also a painter. She lives there with her husband Olek Teslar and their son Antek in a phalanstère, which were agricultural or industrial production and housing cooperatives devised by the early socialist French theorist, reformer and utopian Charles Fourier (1772–1836). Above all, they distribute medicines to the rural population there.

She leaves her husband and stays with de Staël with her son. There are few pictures of her, many are well-kept in private collections. She was probably already a very confident painter when the two met while de Staël was still searching. In 1935 an art critic praised her work, describing her as “virile and nervous”.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait de Jeaninne

Many years later Staël says:

“When I was young I painted the portrait of Jeannine. A portrait, a true portrait, is still the pinnacle of art. "

The family goes back to Paris. They cannot marry because the divorce from her former husband is too bureaucratic. They live in precarious circumstances. In 1939/40 Nicolas de Staël was in the Foreign Legion in Tunisia. When he comes back they go to Nice. Their daughter Anne is born there in 1942. His little daughter inspires him and he now focuses his work on portraits of Jeaninne instead of landscapes. In 1943 the four of them return to Paris. The war years are very difficult. Jeanne Bucher, the courageous gallery owner, helps the family. She also organized de Staël's first solo exhibition in Paris in 1944. He doesn't sell anything, although a lot of well-known painters come to the opening. The reviews are restrained. Abstract art still counts little.

He looks really fascinating, even a painting, a beautiful animal, a painting fox. He has also been called “the Prince”.

Jeannine Guillon died in February 1946 at the age of 37. There is a quote from her while she is in the hospital that sounds like a sinister poem: "I have entrusted my truth to a born liar / who can never tell / he will live it / his brilliant lie to the world will make it tangible." Quote from the broadcast of France Culture: Jeannine Guillou et Nicolas de Staël : la rencontre

The death of his wife, the ongoing financial difficulties, the difficult war years, all of this brought de Staël into a deep depression. A few months after his wife's death, he married Françoise Chapouton. His daughter Anna de Staël describes the situation as follows: “They married in May 1946 without waiting for the paint to dry before applying a new paint. It was the greatest joy next to the deepest pain. And you can say that from this contradiction of feelings he drew a momentary energy that enabled him to progress, to sharpen his way of painting even more.”

In the years that followed, success slowly set in. He meets the American art dealer Theodore Schempp, who distributes his work in the United States. He exhibits with Braque and other well-known painters in the Dominican monastery Saulchoir in Étiollesaus. Braques became a lifelong friend who was very inspiring for him. A painting is bought from him for the refectory of the monastery. He's starting to sell more.

He was naturalized in April 1948. Shortly afterwards, the son Jérôme was born. Anne de Staël sees a connection between the births of children and his way of painting: “The life in his painting gave the ephemeral a feeling of very long duration. Life was the birth of his daughter Laurence on April 6, 1947 and his son Jérôme on April 13, 1948. De Staël's joy over the birth of his children was a deep, intense feeling. The memory of the births, of the moment when the light was poured out. Life is color and energy that makes the flame blaze higher and higher. "

De Staël works continuously on the development of the colors. In this way, the paint applications become thicker and denser, the colors themselves finer.

1949 was an important year for him. He participates in group exhibitions in São Paulo and Toronto. He uses all techniques, all materials: gouache, ink, oil, canvas, paper. And he refuses, like all his life, to be classified in a category. When the Musée national d'art moderne de Paris bought a 1949 oil painting on canvas in March 1950, he didn't want it to be in the abstract group. The painting was then not called “Abstract Composition” but “Composition in Gray and Green”.

Again and again, de Staël was accused of having abandoned abstraction and to have returned to the figurative. His work alternated between figuration and abstraction, sometimes it could oscillate between the two and mix. De Staël always wanted to renew himself.

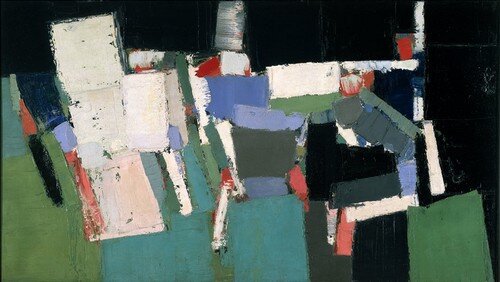

Here you can see eight pictures from the cycle “Les Grands Footballeurs”, which comprises 15 paintings. You can see them very nicely on the website footichiste .

When he and his wife attended the football match between France and Sweden in the Parc des Princes stadium in Paris on March 26, 1952, he was so enthusiastic that he started painting that night. It is one of the first games under floodlights and he was fascinated by the radiance of the colors. A week later he finished the large-format painting Le Parc des Princes, 200 × 350 cm. He used very large spatulas and pieces of sheet metal to spread the paint.

I imagine what it must have been like ... to see a game under floodlights for the first time: exploding colors, a frenzy, the glowing green grass under the artificial, blinding light, because of which the jerseys stand out even more radiantly. And all in a constant movement.

When he exhibited the painting in May of that year, it was viewed as an insult by both his colleagues and critics. One sees in him a manifesto of the figurative, which all proponents of abstraction oppose. De Staël is found guilty of giving up abstract research. He was described by the artist and art theorist André Lhote as a "political criminal".

I’m not an arthistorian, I had no idea of these struggles for the “only true” painting, that there was this dispute among the artists themselves. True artists don't categorize I thought ... I always thought that it was only the new currents who had to struggle with the conservative forces. What would Hans Hartung have or would have said about these fights?

Although André Breton claimed that an artist who was not entirely devoted to the abstract could not be successful, De Staël did not. The New York art dealer Rosenberg offered him an exclusive contract.

Soon he found a new source of inspiration in music. He discovered the “colors of sounds”.

And there are also the colors of the south. With the whole family he traveled in a van to Italy, Tuscany and Sicily, Agrigento. A number of paintings are created there under the name “Agrigento”. They are among his most famous works.

Sicile-Agrigente 1954-Staël : peint à Ménerbes »

Shortly afterwards, de Staël bought a house in the Luberon in Ménerbes, le Castelet. Ménerbes appears again and again as the subject of his paintings. He tirelessly continues to deliver to Rosenberg, who writes in an American newspaper that he regards Staël as one of the safest values of his time.

Indeed, the exhibition on February 8, 1954 at Paul Rosenberg's was a huge commercial success.

For this exhibition, de Staël supplied all the paintings he had painted in Ménerbes in memory of his trip to Sicily, Italy. These paintings with all the colors of the south, flowers, still lifes, landscapes. De Staël worked with an unimaginable energy and produced so many images that Rosenberg had to slow him down by explaining that customers would probably be afraid of such a high speed of production. Angrily, de Staël replies: I do what I want, painting is a necessity for me, with or without an exhibition.

The paintings of the south can be wonderfully viewed here under the link of the exhibition La Provence source d’inspiration de Nicolas de Staël in 2018 in Aix-en-Provence.

On April 3, 1954, Françoise gave birth to a son, Gustave. But the couple was already separated.

Nicolas de Staël had fallen in love with another woman and unconditionally. Laurent Greilsamer writes in his book Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël about him that it was the first time that he loved more than being loved. He was now wealthy from his art, but he remained melancholic and desperate.

Just as the landscapes of the south had inspired him to create the shimmering, shimmering landscapes, his lover Jeanne Mathieu inspired him to create many nudes.

Nicolas de Staël Nu debout 1953

To be closer to his beloved, he moves to Antibes. There are several exhibition projects and he paints obsessively. In the last month of his life he is said to have painted 350 pictures. One critic, whom he asked for advice, said the paintings were too decorative. That hits him hard. He is working on a huge painting “Le Concert” measuring 3.50 x 6 meters. When he finishes it, he kills himself.

In March 1955 he reveals to his foster son Antoine Tudal, formerly Antek Teslar, the son of his first wife Jeannine:

“… I don't know if I'll live much longer. I think I've painted enough. I got what I wanted. "

I see so much strength, courage and dedication in Nicolas de Staël's art. And so much despair shakes me.

I also wanted to mention Godard, who was inspired in a very special way by Nicolas de Staël.

“All my life, I had a need to think about painting, to paint in order to liberate myself from all the impressions, all the feelings and all the anxieties of which the only solution I know is painting.” Nicolas de Staël

“There’s no difference between my life and my movies. I’m existing more when I’m making movies than when I’m not. That’s why someone might say to me, “You have no personal life; I can’t have a relationship with you. When we’re making love, you’re suddenly saying, ‘What a beautiful shot I’m thinking of!’ It’s like a painter only speaking of colors.” But I think what I’m doing is the only thing I can speak of – creation.” Jean-Luc Godard

Godard also said: “You ask me about painting. […] It is an enormous aid. […] In painting, I know of no one who went further then Nicolas de Staël.”

Before Godard turned to cinema, he actually wanted to be a painter. Shortly after his first feature film 'À Bout de souffle’ came out in 1960, Godard declared: “I work like a painter”. In his films he has repeatedly quoted painting, as reproductions, as tableaus, as scenes reminiscent of certain paintings, also by naming his characters. He created his private art history, so to speak (in which there are only male artists, yes, yes it is what it is). Most of this own art history in his films are not contemporary painters. It ends with de Staël's suicide in 1955. In a 1997 interview, Godard was asked which artists he identified with. Godard replied: "Novalis, Nicolas de Staël ... those who died young and tragically."

Godard's fascination for Nicolas de Staël is particularly evident in his film Pierrot Le Fou. He is even mentioned by name: When Marianne and Ferdinand are on the run and the task is to invent stories for people to calm them down, Marianne asks him what kind of stories it should be and Ferdinand replies:

"The fall of Constantinople or the story of Nicolas de Staël and his suicide or that of William Wilson."

The fleeing couple move from Paris to the south of France, mirroring de Staël's own move from Paris to Provence in 1953 and then to Antibes in 1954.

And then of course there are the colors in this film, the colors of de Staël in his pictures from the early 1950s. Blue dominates in the film, but there is a kind of battle between blue and red. The beginning is mostly red, while the end credits are blue. This contrast dominates the film's palette. For example the shot of Marianne Renoir in a light blue bathrobe with a bright red pot or the scene between Marianne and Pierrot next to each other in blue and red sports cars.

The connection to de Staël becomes particularly clear in the final scenes by Pierrot le fou. Make-up artist Jackie Reynal remembers: “For Pierrot le fou, Godard decided to shoot in the town of Porquerolles because of its light and the white there. There the white, the blue and the red are more intense. Hence the idea for Belmondo to paint his face blue - obviously not a make-up artist's idea.”

Movieposter Godard Pierrot le Fou

At the end of the film, Ferdinand has transformed himself into a kind of tableau vivant, like an abstraction of de Staël's life and death. In a red shirt, Ferdinand prepares for his own suicide by painting his face blue, reminiscent of the images of the landscapes of de Staëls in the south of France, such as Paysage du Lavandou (1952).

Nikolas de Staël Paysage du Lavandou 1952

The source for this section on Godard and Nicolas de Staël is the very impressive and detailed article Leap into the Void: Godard and the Painter by Sally Shafto, May 2006 in Senses of Cinema

The next chapter goes back to the original journey, a stroll through Paris to the Greco exhibition in the Grand Palais.